| Contributed by Tim Williams, MD, John Taylor, DO, and William Hickey, MD | |

| Department of Pathology (TW, WH) and Neurology (JT) Dartmouth Medical School |

The patient was a 40 year old woman in good health with no history of headache or migraine until she developed progressively worsening headaches over approximately 5 months. Initially the headaches were dull and throbbing, occurred once per day and in the frontal area, and resolved spontaneously over approximately an hour. In the ensuing weeks she began experiencing lightheadedness and fatigue associated with her headaches, which gradually migrated to the back of her head and neck, had a "stabbing" quality, and were occurring 3-4 times daily. Five days prior to hospital admission, her headaches significantly worsened (described as "10 out of 10" and the "worst headaches of her life"), were keeping her awake at night "writhing in pain," and were accompanied by nausea and vomiting. This escalation prompted her to seek medical attention.

Initially presenting to an outside hospital, her physical and neurological exams were unremarkable. Nonetheless, worry for a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) prompted a head computed tomography (CT) scan, which did not reveal subarachnoid blood. She was subsequently discharged with analgesics. The following day, she represented with continuing headache, and she and was reevaluated, undergoing a lumbar puncture which was suspicious for SAH. She was then transferred to our tertiary care facility for further workup and management.

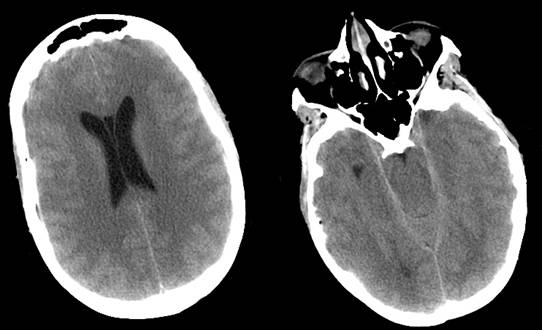

On arrival at our hospital, the patient was somnolent and unable to follow commands. Head CT [Figure 1] and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed bilateral swelling in the cerebral hemispheres. Neuroradiological interpretation was that the findings were most consistent with meningitis, encephalitis, or metabolic disease.

She was admitted to the intensive care unit and started on intravenous antibacterial, anti-viral, and steroid therapies. Subsequently her headaches subsided and she fully recovered over the ensuing several days. However, repeat MRI was unchanged, and extensive lab-oratory studies had not revealed infection, tumor, or any other etiology for her headaches and associated symptoms. At that time neuro-oncology was consulted, and after thorough review of the case their opinion was that this presentation was not consistent with an intracranial malignancy.

On hospital day 6 the patient was discharged to home with a tentative diagnosis of viral or post viral acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

One month after discharge, the patient was seen in follow-up and she reported doing well with minimal headaches. She had resumed her normal activities as a high school guidance counselor and was exercising regularly. Repeat MRI showed no significant change from previous, and a repeat lumbar puncture was normal. No further diagnostic studies were done at that time.

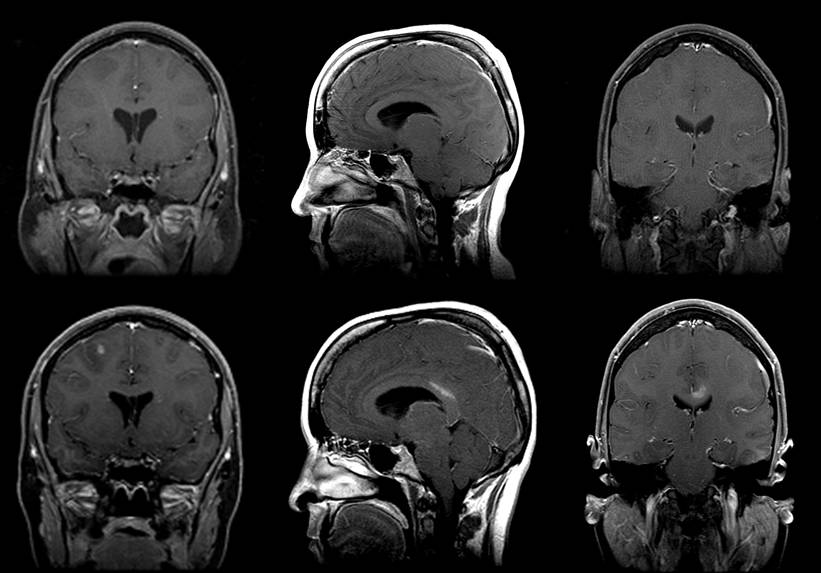

Two months later she had another follow-up MRI [Figure 2]. This showed worsening of the previously noted mass effect, causing effacement of the sulci and downward shift with crowding of the cisterns. There was also a new finding of enhancement in the corpus callosum and a small area of enhancement in the left parietal lobe. Upon neuroradiological interpretation, the possibility of a diffuse brain neoplasm, such as gliomatosis cerebri or lymphoma, was raised. Despite these findings, the patient continued to feel well, be in good spirits, and remain fully active.

The following day, the patient was seen in the emergency department of an outside hospital with return of headaches. These were now described as paroxysmal, sharp and stabbing, occipital predominant, and accompanied by nausea and lightheadedness.

Based on the new MRI findings and recent return of symptoms, neuro-oncology recommended an MR spectroscopy scan.. As the overall appearance of this scan was suggestive of intracranial malignancy, a brain biopsy was recommended.

However, prior to the brain biopsy, the patient developed another sudden severe headache after returning home from kayaking with friends. She was described by a witness as “screaming with her back arched and arms and legs straight and stiff”. Emergency medical services were called. En route to the hospital she lost consciousness and died.

Figures 1 and 2

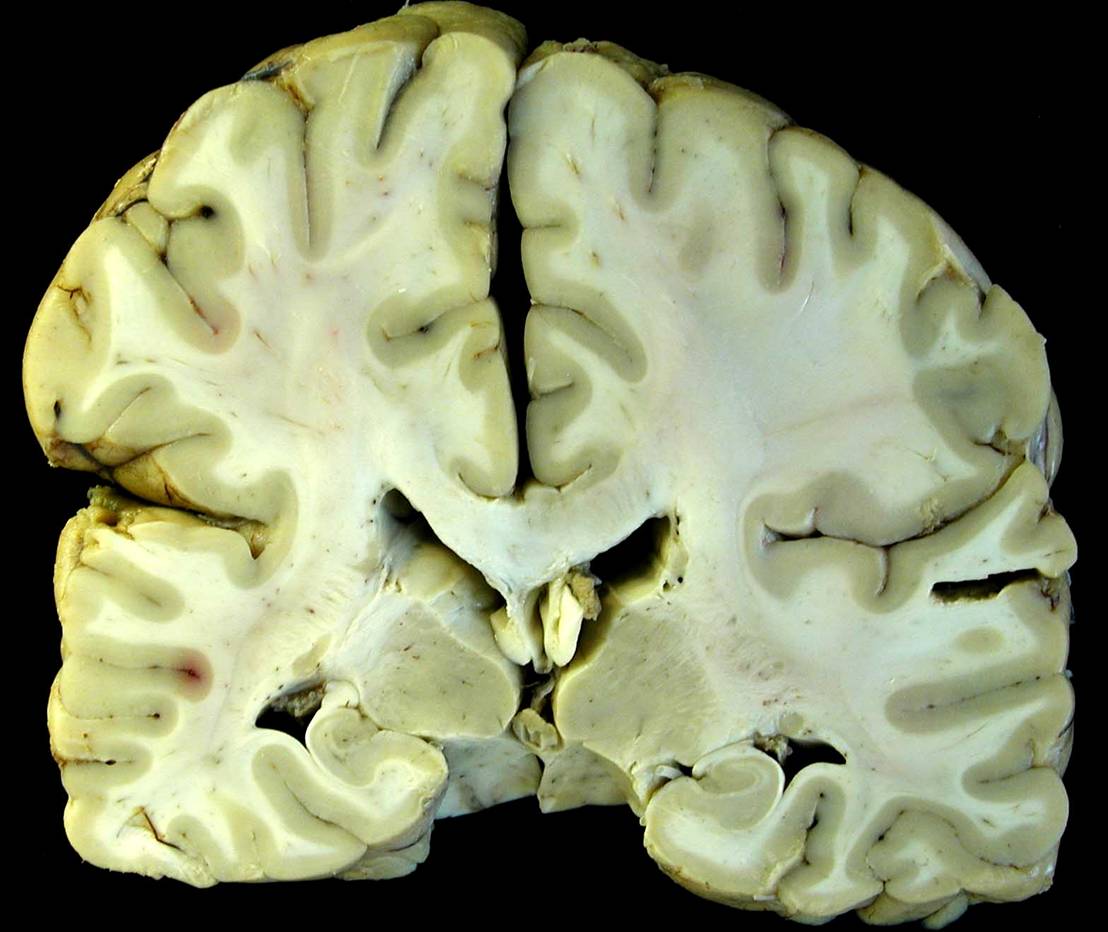

The fixed brain weight was mildly elevated at 1500 grams. The dura was normal. While the gyal-sulcal pattern was normal without frank effacement, subtle expansion of the right hemisphere with slight right-to-left mass effect was evident, particularly on the caudal aspect [Figure 3A]. Mild uncal grooving was apparent, more prominently on the right. Cerebellar tonsilar softness and notching were also noted, more pronounced on the left, which also displayed a dusky discoloration [Figure 3B].

Figures 3

Figures 4

Coronal sections of the cerebral hemispheres showed the right centrum semiovale to be of slightly greater apparent mass than the left [Figure 4]. There was subtle expansion and dark discoloration of the right side of the corpus callosum. Serial horizontal sections of the brainstem displayed mild expansion of the right mesencephalon and pons, and areas of duskiness suggestive of early Duret hemorrhages [Figure 3].

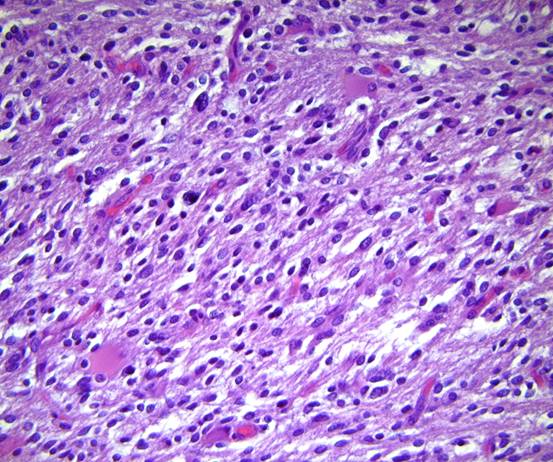

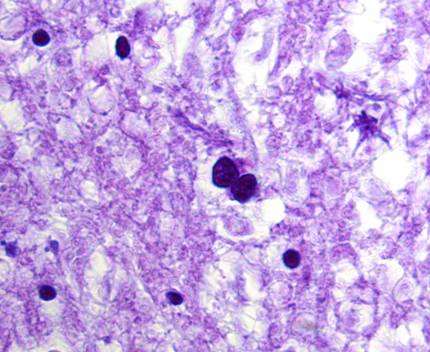

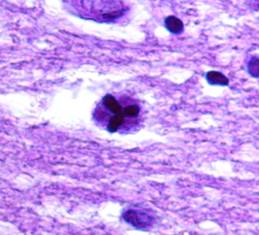

Microscopic examination revealed diffuse infiltration of poorly differentiated, anaplastic glial cells, with frequent tumor cell clusters and occasional apoptotic cells, most prominently in the right centrum semiovale, right striatum, and right posterior corpus callosum [Figure 5A-C]. Infiltrating tumor extended into the left frontal and left parietal lobes. Rare atypical cells suspicious for tumor were also encountered in the white matter tracts of the mesencephalon and pons. Marked white matter edema was present in the right and, to a lesser extent, left frontal lobes. The cerebellar tonsils were mildly edematous, with the right showing focal spray hemorrhages into the neuropil.

Figures 5A-C

Figures 5A-C

Based on the findings from general and neuropathological autopsies, the cause of death was determined to be acute transtentorial and foramen magnum herniation secondary to mass effect from cerebral edema and diffuse tumor infiltration.