| Contributed by Brent T. Harris MD, PhD and Timothy Williams, MD | |

| Department of Pathology (Neuropathology), Dartmouth Medical School |

CLINICAL HISTORY:

A 58 year-old male presented in a minimally arousable state several hours after experiencing right-sided paresthesias and nausea accompanied by vomiting. These symptoms occurred on a background of several weeks of episodic right- and left-sided numbness and paresthesias, which resolved spontaneously after a maximum of 30 minutes. He had a distant history of esophageal carcinoma for which esophagogastrectomy with re-anastomosis and local radiotherapy were performed. In the intervening 14 years, he had required esophageal dilation three times, most recently approximately one month prior to the current presentation. Past history also included an episode of idiopathic pericarditis three years prior to presentation.

On admission to a community hospital emergency department, the patient was somnolent yet arousable and able to follow commands. His blood pressure was 70/40 mmHg, heart rate 110 beats per minute, and temperature 39.4 degrees Celsius. Initial investigations were notable only for anemia (hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL), and a chest X-ray was interpreted to show mild, patchy bilateral infiltrates. Over the ensuing 24 hours, the patient's white blood cell count, initially normal, increased to 31.2; a head computed tomography (CT) scan showed multifocal areas of decreased attenuation most consistent with embolic infarctions; a transthoracic echocardiogram was suspicious for a tricuspid or aortic valvular vegetation; and gram positive cocci (later identified as S. aures and H. influenza) were isolated from blood cultures. A presumptive diagnosis of sepsis from pneumonia and possible bacterial endocarditis was treated with antibiotics. When the patient's status did not significantly improve over the ensuing 36 hours, he was transferred to our tertiary care medical center for further evaluation.

The patient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Multiple subspecialties were consulted, and the consensus diagnosis was probable infective endocarditis with embolic cerebral infarctions. Repeat blood cultures again grew S. aures and H. influenza, and later Candida albicans. Cardiology services initially recommended transesophageal echocardiogram to confirm a cardiac source for the emboli; however, distinct visualization of the esophagus by upper endoscopy revealed altered geometry and prohibitive esophageal stenosis. Subsequent intra-cardiac echocardiogram did not demonstrate valvular vegetations or intra-cardiac shunting by bubble contrast.

Repeat noncontrast head CT showed multifocal areas of decreased attenuation,

many with centrally placed pockets of air (Figure 1). Given the presumptive

diagnosis of endocarditis, these findings were thought to be most consistent

with septic emboli and resulting intracerebral abscess. The following day, magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to further evaluate the extent and age

of the cerebral infarcts. A striking feature noticed at that time was absence

of the previously demonstrated air pockets (Figure 2), indicating either rapid

reabsorption or eradication of gas producing organisms. Numerous areas of restricted

diffusion consistent with acute infarct were noted, particularly in the right

parietal region, which had shown air pockets on previous CT scans. No rim enhancing

lesions were present, reducing the likelihood of abscess and bringing air embolus

as a cause of acute cerebral infarction to the top of the differential diagnosis.

However, no source for air emboli was apparent, particularly in the absence

of intracardiac shunting by echocardiography.

Initially fluctuating between periods of minimal responsiveness and obtundation,

the patient's mental status improved over the ensuing week, with intermittent

periods of wakefulness and lucidity. On multiple antibiotic regimens, his white

blood cell count had normalized and he no longer required pressor or airway

support. Despite earlier difficulty, a transesophageal echocardiogram was performed,

and failed to show valvular vegetations and again did not reveal intracardiac

shunting.

The patient subsequently experienced several episodes of hematemasis, and heme-positive stools were later noted. On hospital day 12, his condition acutely worsened, with spiking fevers, leukocytosis, respiratory distress, and obtundation. By this time, infective endocarditis was considered unlikely.

On hospital day 15, a stereotactic brain biopsy of one of the infarcted lesions

was performed, and showed necrosis with reactive changes and hemosiderosis consistent

with subacute infarction. Evaluations for vasculitis, thromboemboli, and microorganisms

were negative. A cerebral CT scan showed continued embolic disease and cerebellar

tonsilar herniation. Over the ensuing 24 hours, the patient's condition deteriorated

to the point of brain death, and supportive measures were withdrawn. Permission

for an unrestricted autopsy was granted by the next of kin.

RADIOGRAPHIC IMAGES:

Figures 1 and 2

PATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS:

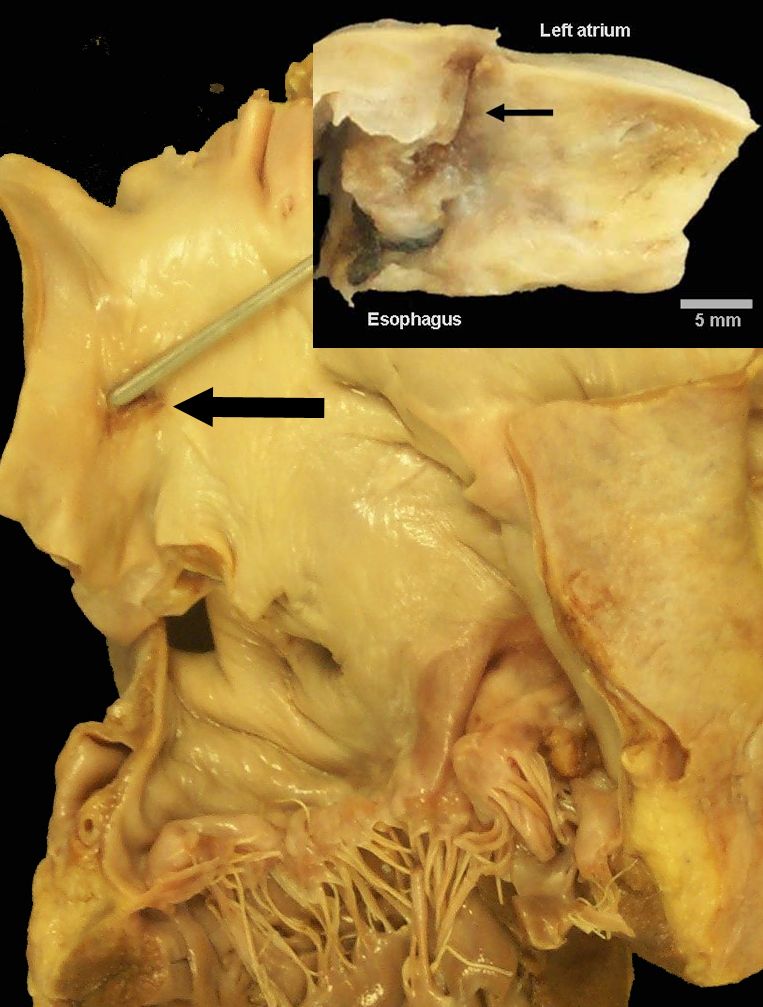

Autopsy. Post-mortem examination revealed severe scarring and esophageal stricture

at the site of prior esophagogastric anastomosis. Thorough histological examination

of this area did not show recurrent carcinoma. Para-esophageal tissue was densely

fibrotic and adhered to adjacent structures, including the pericardium. The

pericardium itself was diffusely adhered to the epicardium, obliterating the

pericardial space. A probe-patent fistula between the esophagus and left atrium

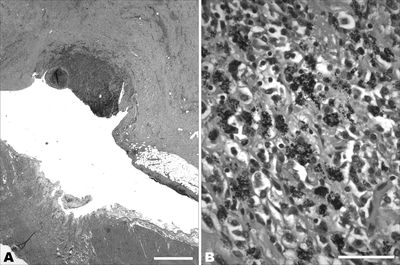

was identified at the site of esophageal-left atrial adherence (Figure 3). Histological

examination of the fistula tract showed it to be lined with chronic inflammation

and granulation tissue, extending from the denuded esophageal mucosa to the

left atrial endocardium (Figure 4A). Along the fistula tract was precipitated

carbon-like material within the interstitium and in the cytoplasm of macrophages

(Figure 4B).

Figures 3 and 4

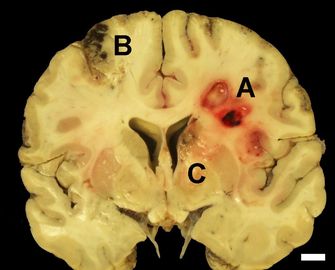

The brain was diffusely edematous with multiple, variably-sized hemorrhagic infarctions and areas of softness on the cortical and cerebellar surfaces, including the cerebellar tonsils. On coronal sections, focal obscuring of the cortical grey-white matter junction was apparent, and multiple acute and subacute embolic infarctions were present in every major arterial distribution (Figure 5). Some of these areas were cavitary and by microscopy contained red blood cell ghosts. Stains for micro-organisms were negative.

Other findings included acute and subacute embolic infarctions in the myocardium,

kidneys, and spleen.

Figure 5