emory

uschwitz

nspeakable

tories

~ New Way of Reading and Writing: Part II~

Tomoko Yamazaki

Georgetown University

American

Literary Traditions

* This is a hypertext essay which allows one to read in

whatever fashion. This following text is the Part II of the previous

essay on the novel Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko. Please feel

free to explore the text in any way you would like to read; there is no

one "absolute" way of reading the following text.

Introduction

The title of an award winning holocaust literature MAUS by Art Spiegelman

may stand for the following four words: Memory, Auschwitz, Unspeakable,

and Stories. The book tells us the story of a Holocaust survivor

through Speigelman's interview of his own father. Although the book is

written, or rather drawn, in a comic fashion, the content of this comic

book is far deeper than one can imagine. Toni

Morrison spoke the following in her speech given at the acceptance

of the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to

American Letters in 1996:

There is a certain kind of peace that is not merely the absence of

war. It is larger than that. The peace I am thinking of is

not at the mercy of history's rule, nor is it a passive surrender to the

status quo. The peace I am thinking of is the dance of an open mind

when it engages another equally open one--activity that occurs most often

in the reading/writing world we live in. Accessible as it is, this

particular kind of peace warrant vigilance. . . . Underneath the cut of

bright and dazzling cloth, pulsing beneath the jewelry, the life of the

book world is pretty serious. Its real life is about creating and

producing and distributing knowledge; about making it possible for

the entitled as well as the dispossessed to experience one's own mind dancing

with another's; about making sure that the environment in which this work

is done is welcoming and supportive. It is making sure that no encroachment

of private wealth, government control, or cultural expediency can interfere

with what gets written or published. That no conglomerate or political

wing uses its force to still inquiry or reaffirm rule. Searching

that kind of peace--the peace of the dancing mind--is our work, and, as

the woman in Strasbourg said, 'There isn't anybody else. (The Dancing

Mind)

Spiegelman's "Dance of an open mind," with which he explores the

unspeakable past of his father in a unique fashion, the readers are allowed

to engage themselves into the pleasurable act of "reading." I would

like to explore this new style of writing in the order of the four words

that may be derived from the title itself.

Next>>

I. Memory: How Human Beings construct memories

~ Cyclical or Linear ~

In one of the interviews, Spiegelman speaks of the construction of

people's memory as something that is non-chronological. When

one is asked to speak about the memories of his/her high school days, one

may begin by speaking about the most memorable events in his/her high school

days, which will not necessarily come in a chronological order. He/she

may start by sharing about the prom night, and then the Homecoming games,

and then the tournaments that one might have participated.

Clearly, the way in which we recall the memories of the past is not always

"chronological" ; different events and matters have different meanings

to each of us, which makes our memories non-linear unlike a timeline in

a history book. As Vladek, Art's father, remembers and speaks of

his past experiences, we see how Art struggles to get the stories from

him in chronological order.

The way in which Vladek struggles to recall the painful memories in order

might be a reflection of the two kinds of memories clashing into each other:

Deep Memory and Common Memory. In the book Holocaust Testimonies:

The Ruins of Memory, by Lawrence Langer, Langer speaks of these two

memories as the following:

Deep memories tries to recall the Auschwitz self as it was then;

common memory has a dual function: it restores the self to its normal pre-

and post camp routines but also offers detached portraits, from the vantage

point of today, of what it must have been like then. Deep memory

thus suspects and depends on common memory, knowing what common memory

cannot know but tries nonetheless to express. (6)

The stories that Vladek "reremembers" at Auschwitz are something that are

stored in his deep memories, and when he speaks of it, although it is still

hard to recapture every moment that he is speaking in its fullness, he

tries to do so; however, the difficulty of bringing the stories back to

life with his common memory is a challenge for the speaker, because of

the fact that Vladek himself has already outlived the struggles at Auschwitz.

Living in this society today, the survivor faces a difficulty of actually

facing what he/she had done in order to survive in Auschwitz. There

is no one to condemn him/her for what one did, however, the whole event

appear to the survivor as something hideous and humiliating now that one

is liberated. Thus as we see in the book, Vladek tends to go off

tracks and speak of the horrible past rather in an unemotional manner.

One of the survivor speaks in the Memories

and Visions Section of Prologue of L'CHAIM his guilt of surviving

the Holocaust as the following:

I am also concerned about my sons. I have never told them anything

about my life. How will they respond? They have never asked, and that was

fine with me, for I never felt worthy to have children that loved me, because

I am not able to forgive myself for having survived. Survivor's guilt is

so insurmountable, that it becomes a factor in coping with life; from that

moment on.

On the other hand we see a son who tries to keep his father on track so

that he will speak the memories chronologically in order to fulfill his

desire of keeping the memory

alive. John

McGowan writes in his essay on MAUS as the following:

"One of the most frequent themes in the lives of the children of

survivors is the desire to keep the memory alive." Art's act

of actually writing this "Survivor's Tale," is not only to recapture the

horrible event of the Holocaust, but it is also for him to try to fulfill

his desire of being able to feel the "pain" which his father felt back

in the old days. What we see as a wall between Vladek and Art is

not a simple generation gap: it is a desire to "experience" the unspeakable

past. At one point Art portrays himself wearing a mask of a mouse and

telling Pavel after his father's death the following: "No matter what

I accomplish it doesn't seem like much compared to surviving Auschwitz"

(46). We see the one who tries to capture the memories in its fullness

feels overwhelmed by the power that each of the memory enhances, which

leaves a child of a survivor inferior to his father and rather helpless.

As a matter of fact, we see how Art's portrayal of himself when being interviewed

gets smaller like a tiny baby mouse, and visually, we are convinced that

Art feels "smaller" not only against the "memories" that his father speaks,

but also against his father. As Antonio

Oliver says in his essay on MAUS, "The evil past of the Holocaust

is unspeakable, unexplainable, but above all, unforgettable."

Remember

that it is easy to save

Remember

that it is easy to save human lives.

. . . In those times, one climbed to the summit of

humanity by simply

remaining human.

Elie Wiesel,

THE COURAGE TO CARE (p. xi)

human lives.

. . . In those times, one climbed to the summit of

humanity by simply

remaining human.

Elie Wiesel,

THE COURAGE TO CARE (p. xi)

Go

to Ceremony Paper on Memory>>

Next>>

II. Auschwitz: Oral and Written History

I have always believed that human beings are one of the best texts

in life. In The Survivor's Tale: MAUS is Art Spiegelman's attempt

to write a book of a horrible event in the human history, the Holocaust,

using his father's Oral history as a source. In the essay,

Of Mice and Memory, Joshua

Brown calls Art Spiegelman as "a skilled oral historian." Throughout

the book, not only do we see Art acting as "a skilled oral historian,"

but also we see how he tries to obtain the information in a more "written

history" manner; that is, he tries to obtain the stories in chronological

order as if he was trying to write a section on Holocaust in one of the

history texts. The stories of the horrible past reach the readers going

through two levels. One is Art's conversation with his father which

is the actual acquiring of the Oral history, and the second is Art's interpretation

of his father's "Oral History." In the CD-ROM version of MAUS how

Art goes through several rough drafts in completing the final draft; each

time the words in the bubbles change, and as a matter of fact, they

sometimes differ from the tape-recording of the interview with Vladek.

It is important that the "oral history" may "evolve" in its natural manner,

because what is spoken by the "speaker," and the interpretation of it may

differ with each "listener." However, this does not mean that the

history itself loses the accuracy of the events; one has to come to accept

that there is a different fashion through which history has to be carried

through, and "Orally," is just one example of it. In the interview

with Brown, Art comments on the difficulty of keeping the "Oral

history" linear:

This is my father's

tale. I've tried to change as little as possible. But it's almost impossible

not to

[change it] because

as soon as you apply any kind of structure to material, you're in trouble--as

probably every

historian learns from History 101 or whatever. Shaping means [that] things

that

came out [in

an interview] as shotgun facts about events that happened in 1939, facts

about

things that happened

in 1945, they all have to be organized. As a result, this tends to make

my

father seem more

organized than he was For a while I thought maybe I should do the book

in a

more Joycean

way. Then I realized that, ultimately, that was a literary fabrication

just a s much

as using a more

nineteenth century approach to telling a story, and that it would actually

get

more in the way

of getting things across than a more linear approach.

With "oral history," one has the advantage not to leave things out; one

is capable of putting things in, such as the conversations between Art

and Vladek we see in the book, that is off-track from the actual Holocaust

accounts. The history comes out of Vladek's mouth with life of its

own, and Art interprets them to turn them into a "written and drawn" history,

which is the completion of this piece of art MAUS. Although in our

society today there is a fixed notion of how history can only be legitimized

when it is "written," when we go and read some of the books written on

holocaust, we realize how they might be misleading one to a history without

any "life" of its own except for "denial."

"In Auschwitz wurde niemand vergast."

"In Auschwitz wurde niemand vergast."

written by Markus Tiedemann ("Nobody was gassed

at Auschwitz.": 60 Rightist Lies and How to

Counter Them"),

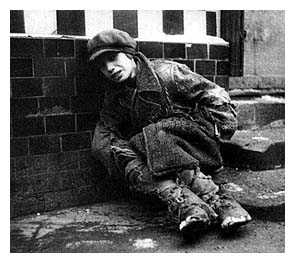

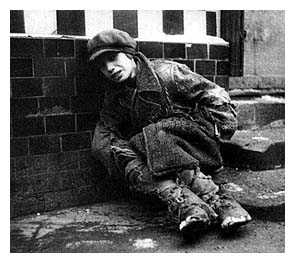

A starving boy. . .

Go

to the Ceremony Essay on Oral/Written History>>

Next>>

III. Stories and Storytellings: Unspeakable Stories

In the Atomic Memories section of Remembering

Nagasaki, there is a comment as the following on the stories he

heard from her mother about the bombing of Nagasaki:

It never seemed completely real to me. I think my mother's matter

or factness had something to do with that. It wasn't that I didn't think

it was horrible -- I knew and felt that it was -- it just seemed very far

away -- very far removed from my existence and the things I felt were real

(I am speaking of the time when I was about 5-6 ).

In her comment he said that all he got from his mother about the bombing

was that "she was not harmed at all -- but lost a cousin and an uncle,"

which shows no emotions, but facts. Now, can we say that his mother

had no feeling of terror as she spoke about the horrible past? When

one tries to recall something so horrible in one's life, it is often the

case that one tends to simplify the event so that it is bearable; or sometimes

one would never speak of the "unspeakable stories" of the past. In

one of the responses to Beloved and various Holocaust sites, one of our

classmates (anonymous essay #3) wrote the following:

It seems that in reference to Beloved, people "speak about the unspeakable"

in the most matter-of-fact terms as possible; as if to avoid an emotional

recollection of the horrible event. These "unspeakable" memories are often

recollected in a fragmented form, as if they are unnaturally forcing themselves

into the consciousness of the character whenever an experience allows them

to do so.

In MAUS, we clearly see how the stories of how Vladek survived the Holocaust

is the most important thing in constructing the book. Although Vladek

speaks about something so painful that makes it "Unspeakable," we see how

through his telling the stories, not only does Vladek begin to admit that

this really happened along with the death of Anja, but also Art beginning

to accept the horrible past as well as accepting himself for not being

able to experience what his father had gone through. As we see in

MAUS, it is true that by telling the "Unspeakable stories," the healing

process follows, and we see the "storytelling" serving as a "healing process,

more through Art's act of actually putting his father's stories into one

book.

It is Art Spiegelman's way of telling the "Unspeakable stories" with a

unique form that makes the book outstanding; with the several layers of

paintings, the daily conversations between them, masking of the characters

as animals, and finally allowing the readers to peek into even the process

of Art creating the book, Art indirectly gives the history of the Holocaust.

Moreover, not only does MAUS serve as a great example of presenting the

importance of the "act" of storytelling, but it is also "about" storytelling.

The whole book is reflective on Vladek's words, and those each words carries

meaning as they are spoken. Art receiving those words become connected

not only to the past, but also to his father closer than ever. By

reading the book, we are able to hear the stories of the Holocaust through

Vladek, but also the stories of how a son and a father becomes united through

the act of "storytelling," by its very form of the book. Doug

Boin cites the following in his essay on MAUS:

The importance of oral

history ( click here and check out the oral history of the survivors)

is clearly seen in this relationship. In Melus, Staub argues that without

talking about the past, these two would, in fact, have no relationship:

'MAUS clearly documents how the son's ambivalence towards the father in

the present immensely complicates the work of reclaiming and representing

the world of Vladek's past' (Staub 34).

Unlike the diaries of his mother, Anja, that were burnt and destroyed by

Vladek, the words that Vladek spoke will remain in Art's mind and

heart as well as ours. The unspeakable stories that are bled with the blood

of Vladek and other countless Jews will continue to be carried through

overtime.

Go to the Ceremony paper on Stories and Storytellings>>

Go back to Introduction>>

Go back to Memory>>

Go back to Oral/Written History>>

Remember

that it is easy to save

Remember

that it is easy to save

"In Auschwitz wurde niemand vergast."

"In Auschwitz wurde niemand vergast."